Abby and Wendy - Episode 36

AN UNUSUAL MEETING

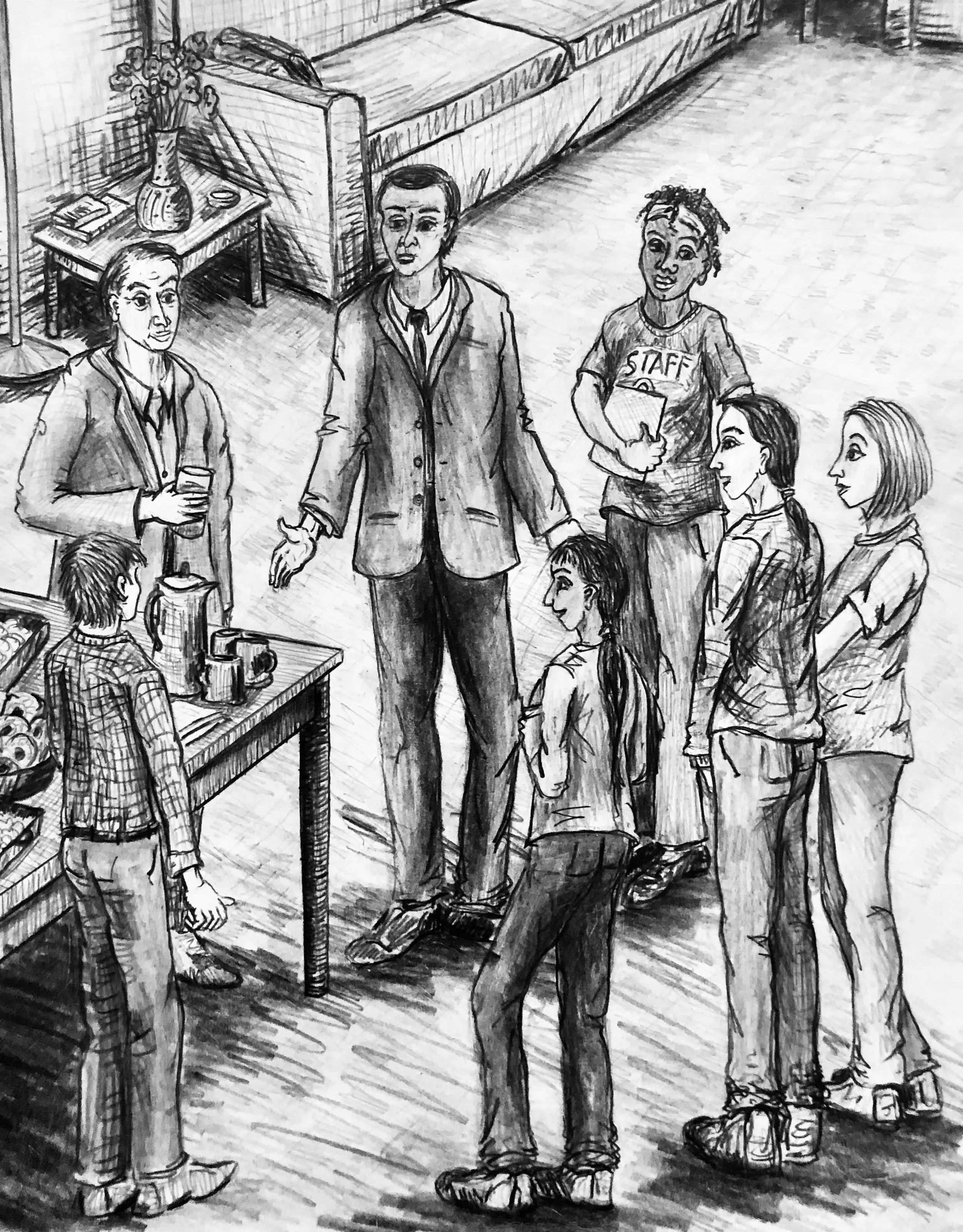

Illustration By Carlos Uribe

Lluvia slowly steered the canoe toward the right bank. A wide view of Evansville opened up before their eyes. The river seemed to grow and spread out, creating space for many docks lining the shoreline. The tall buildings were all on the left side. On the right-hand side a long finger of parkland extended along the shoreline all the way from Half Moon. The Evansville College of Arts and Sciences was nestled among tall trees like a town of mostly low buildings. Beyond the college, Riverside Boulevard ran all the way to River City.

Docks owned by the Parks Department and the College clustered together, creating a marina of boats, all quite small by ocean standards. The depth of the river was only about 5 to 8 feet, and varied radically with rainfall and the tide. No large yachts or ferryboats could safely navigate the river until the Maywood River joined the Half Moon a few miles downstream. At that point the river became wider, deeper, and crowded in a more urban landscape, climaxing at the great metropolis of River City.

Lluvia maneuvered the canoe along crowded docks to a separate, spacious area owned by the college. They tied the boat to cleats in the wooden platform and a young man in a college tee shirt gave them a hand up. Lluvia told him their business and departure time Sunday morning. He wanted student identification, and for a moment they were stuck, unsure what to do.

Then they heard Abby’s name called, and Sara came rushing up the dock. She was obviously nervous and impatient. “Where have you been?”

“Sorry, sorry,” Phoebe answered. “An emergency, and my phone is gone. None of us have a phone. I’ll tell you more later.”

“Hi Bill,” Sara greeted the dock attendant. “They’re all with me, meeting in the energy building with Professor Richardson. He’ll approve it.”

“We picked up a stray boat,” Lluvia said. “It was floating free a mile upriver. Can you look for an owner?”

In a moment the three visitors and Sara were hurrying across a wide pathway onto the college campus. Old buildings, generally only two stories, were spread out among trees and lawns, and connected by flagstone paths. Abby had never seen anything like it. Wisteria grew up old stonewalls, and discreet signs were posted to guide visitors. The scene was calm and lovely in the early evening shadows. But Sara led them at a furious pace. Phoebe lagged behind, pulling her right leg stiffly forward.

Abby checked her timer. “Hey Sara,” she called. “It’s only 6:30.”

“We’ve reserved the private meeting room starting at six. Ricardo Richardson and a grad student and Freddy Baez are there already. We’ve made a dinner reservation for seven o’clock. This is a big deal. And we’re running out of time.” She’s the organizer, the mover and shaker,Abby told herself. Just follow along.

They practically ran through a maze of buildings where students walked in and out of dormitories and gathered in groups on the lawn. Cars full of arriving students and their luggage jammed the courtyard. Finally, Sara led the group to a modern one-story building with a picture window, glass doors, and wings built out from both sides. A limestone porch with benches and potted gardenias surrounded the main entrance. An elegant bronze sign read, ‘Energy in the Age of Climate Change’.

Groups on the benches said hello to Sara and stared as they hurried by, practically running down a carpeted hallway to wooden double doors. A quiet living room spread out before them. Lamps on poles, couches and easy chairs, bookshelves, paintings, and a sideboard of refreshments were scattered around a wide area. Three men stood to greet them.

Sara took charge. “Professor Richardson, Evansville Record editor Freddy Baez, and assistant professor Henry Tims, this is Abby, Phoebe, and…” Sara waited for the name.

“Lluvia,” Abby told them. They shook hands.

“Call me Ricardo, please. We’re here to talk as equals. Can I get you some coffee, wine, tea, club soda?” The visitors asked for coffee, and Ricardo served them himself.

Freddy showed them to a long couch with a coffee table, and looked at his watch. “Can we delay dinner half an hour at least?” he asked Ricardo. “We need the time.”

“Henry, see if they can give us until 7:30. Tell them we apologize, but it’s important.”

Ricardo Richardson, the host and head of the department, wore a dark tailored suit and a pale blue tie. He was tall and lean, in his forties, brown skinned, with black hair cut very short. A gold ring with a small blue stone glowed on his right ring finger. Freddy Baez did not seem to be concerned about his appearance. He looked just the same to Abby as he had appeared in Reverend Tuck’s office: balding, in his fifties, needing a haircut around the ears, a bit overweight, wearing a shabby pale suit with no tie. He sipped his wine and glanced around impatiently.

Henry Tims looked maybe 25 or 26 years old, very young for an assistant professor. He was short and light skinned, with wispy blond hair falling over his forehead, and a vulnerable baby face free of wrinkles. His jeans and pinstriped shirt were clean and ironed, giving him a bit of formality.

“Yes, right away,” he said, and hurried out the door.

Abby and Phoebe were struggling to keep their eyes off the blue stone in Ricardo’s ring. It’s dreamstone, its dreamstone!Their thoughts were buzzing, and they met each other’s eyes with a look of elated recognition. Here’s someone on our side, they thought. Abby glanced at Lluvia and noticed her wide-eyed look. She knows.

Sara retreated to a corner of the room and made a quick phone call. She wore her usual uniform: STAFF tee shirt, jeans, and wide red headband. “Amy will be here in a minute,” she told them.

“Ah! Excellent.” Ricardo gave a sigh of relief. “Let me give all of you a chance to drink your coffee and relax.” He spoke slowly and gently, with the hint of a Spanish accent. “I want you to know how grateful we are to see you here on our home turf. It’s a tremendous favor. I know you’ve overcome obstacles to be here… you folks are under a microscope these days. But now we have a chance to put our minds together in hopes of a better future. This is a moment blessed by fate.”

Henry returned, nodded to Ricardo, and pulled up a chair.

“We’re just getting started,” his professor told him. He was silent for a minute as the young women drank coffee.

Well, well…thought Abby. Quite an introduction. She was determined to play her role with all the concentration at her command, and bring in Phoebe and Lluvia to offer all those things that she could not.

The door suddenly opened and Amy Zhi walked into the room. Sara hugged her, and introduced her to Lluvia and Phoebe. Amy waved to all and sat in an upholstered armchair to the side of the couch. Henry hurried to get her a cup of coffee.

The professor met everyone’s eyes and began: “I think we’ve all done a good job of arranging this off-the-record meeting, and I think we can count on each other’s confidentiality.”

They nodded.

“Please bear with me while I give a brief description of our situation. We’ll be discussing renewable energy developments that are still in an early, fragile stage, but are becoming too prominent to ignore. As you know, tomorrow the Evansville Board of Trustees will be responding to our student/faculty declaration of climate change commitments. I realize that this document is technically open to change and negotiation. But most of us, including the trustees, are aware that we are drawing a red line, a firm position that we intend to implement with all the influence we can find.”

He paused and drank from a glass of wine. “Okay, now here’s some news. We’ve obtained through the grapevine a summary of the trustees’ response. They will point out that not only our college, but also our city and state, are nowhere near ready to achieve %100 renewable energy. Therefore they – the trustees – will not promise to withdraw all fossil fuel related investments. They will say we are decades, thirty years at a minimum, from banishing fossil fuels from our economy. Therefore, they must continue to invest in enterprises that are currently essential to the welfare of our population, such as fossil fuel heat, transportation, electricity, fertilizer, plastic, and so on. We know that this argument is shared by many of the powers that be in our world, and could have merit, except that over the past thirty years they have done nothing except continue business as usual. And the business interests that the trustees represent have no wish to change, and are ignoring the perilous consequences of delay.”

“Hurry it along, Ricardo!” interrupted Freddy Baez. “We’re from the news business, we’re used to rushing. And in twenty minutes we’re supposed to be eating dinner.”

“I understand, Freddy. But tonight, I don’t care if all the food is overcooked or stone cold. I’ve been waiting a long time for this day. Everyone will get a chance to say their piece.”

He took another swallow of wine. “In maybe ten years, with supporting policies like an escalating carbon taxes, regulations, and investments into solar and wind projects, electricity could be just about 90% renewable. But as we know all too well, our state and nation and most of the globe, do not have the political will to achieve anything drastic at the moment. We don’t have the batteries yet to store enough energy to get through days with no wind and winters with little sun. Without the invention of better batteries, generators will need to continue using natural gas at least part of the time. We don’t have the grid, the heating and cooking equipment, the cars and jet fuel and household appliances to move to 100% renewable, even with a carbon tax and enormous subsidies. And for all those places off the grid the situation is hopeless. Propane tanks populate the countryside like mushrooms. And world-wide, that adds up to an insurmountable problem…except for one thing. The problems look different if you include biogas.

Ricardo looked around the room. “That’s what we need to discuss tonight. We know that all organic material can produce biogas, mostly methane. We know that landfilled organic material gives off methane into the atmosphere where it becomes a greenhouse gas. We know that landfilling organic material is expensive. We know that biogas is much more environmentally friendly than burning wood and related materials. We know waste organic material can be collected from a village or a city or a farm. We know the production of biogas can be a local enterprise or a colossal industry. We know that fracking can be banned as soon as we have better batteries for electrical storage and biogas for furnaces, stoves, and generators. Millions of families already use it all over the world. And tonight, we need to talk about the little-known fact that biogas is used by thousands of households right here in the Half Moon Valley. How did this happen, given the political and business support for fossil fuels? Why can’t we study and discuss it?”

The participants looked at each other, but no one answered. Ricardo waited, and then went on: “We’ve discovered that one of our trustees, Herbert Irving, is alarmed that his Valley Fuels distribution network is losing customers. He’s already investigating the production of biogas by our Parks Department. We know he will convince the governor and his allies to close down that operation unless they meet very strong resistance. We know that Rivergate is already 100% renewable, and Half Moon maybe 50% renewable, and Middletown is rapidly getting into the act. Why can’t we replicate this process? Why can’t we argue that with intelligent biogas production – by intelligent, I mean refusing to grow crops for biofuels on land suitable for food crops, refusing to cut down forests… in other words, producing biogas only from waste, organic garbage, wood that is already being chipped by the Parks Department as a matter of ordinary maintenance, grasses grown on land with soil too poor for human food… Why can’t we study, publicize, and argue for intelligent biogas production?”

He looked at his watch. “Thank you for your patience. The ball is in your court.”

“We’ve got a problem among the students,” Sara replied. “They’re all fired up about Abby’s interview, the mysteries surrounding Middletown, the gender and spiritual issues… but… it seems that they don’t understand biogas very well. It’s not clean and pure like solar and wind. It burns and gives off carbon dioxide, just like fracked gas.”

“Mmmm…” Ricardo smiled. “Tell them the squirrels and the dogs and humans give off carbon dioxide. The tree that falls in the forest and turns into compost gives off carbon dioxide. Cow manure gives off carbon dioxide. But the fracked gas didn’t have to give off itscarbon dioxide. It’s been safely underground for millions of years, and could have stayed there, if we didn’t mine it and burn it. We’re adding carbon to the life cycle, carbon that has been sequestered for eons. That’s the problem. We should stick to our basic talking points: KEEP IT IN THE GROUND. BAN FOSSIL FUELS. And by the way, the organic material that produces biogas has a desirable byproduct: solid compost, pure and ready to use as fertilizer. It’s far better to make biogas out of organic material than to burn it.”

“It seems to me,” Sara retorted, “that you should get those professors in first year earth science to do a better job. The facts seem self-evident to you, but not to most other people.”

“Good point. Yes, a better education is essential. But that will take time, a year at a minimum. We need to act over the next couple of months.”

Freddy Baez leaned forward. “I’m sorry to say this, but you’re all on the wrong track. Sure, improve education, explain the issues, argue your case. But we’ve got hot news here, very hot. That interview with Abby… it’s gone around the world. The attention of the public is at a peak I’ve rarely seen. This wave of interest must be fed, or it will break and disappear. News items are stories. What story should we tell? I ask you, Abby… what story would you recommend?”

She had been waiting for this moment. Her mind was well prepared, the words on the tip of her tongue. “I agree we have to move fast. This public attention you’re talking about… it also includes the wrong kind of attention. It alerts our enemies, and they investigate and create their own story. That’s natural. They’re threatened. This Herbert Irving you mentioned who runs Valley Fuels, he’s losing money. Large parts of this whole system will lose wealth and power, and strike back. And fossil fuels are a cultural as well as an economic problem. The self-esteem of part of our population seems to be married to fossil fuels. If we don’t get our story out there in a powerful way, we’ll be crushed.”