Phoebe Comes Home - Episode 16

Episode 16

THE BLACK ARROW

Phoebe pulled herself up off the porch and pushed open the door.

“Is that you, Phoebe? Mom called!” Her sister was yelling from the kitchen. “We’re invited for dinner to the greenhouse.”

Phoebe bounded across the living room in her best speed-limp to hear the details.

After a long walk along Main Street Penny and Phoebe arrived at the enormous old greenhouse behind the Garden Center. Instead of knocking, Penny just walked up to the door and opened it, calling, “Mom! Dad! We’re here!” as she entered. Phoebe followed. They wove their way along a narrow path between plants and small trees, and suddenly arrived at a brightly lit open space where Patti and Peter Hood stood waiting. Phoebe immediately felt the presence of her mother, who gave Penny a kiss on the cheek, and quickly moved on to embrace Phoebe. Patti Hood was a small woman, barely over five feet. But her air of independence and superiority gave her an aristocratic presence, as if she were somehow above the common run of problems. Peter Hood lingered in the background, unable to hide the lines of worry on his huge face.

Penny had advised Phoebe on their walk to the greenhouse to “Go easy on Dad. You know how he worries. He feels bad about the toy store, especially now that you can’t play soccer anymore. I’m pretty sure he thinks he let you down.” This was news to Phoebe. She didn’t realize her dad had taken the knee injury so hard. But of course he understood it. He never missed a soccer game when I was in high school. He knew what it meant to me.

Phoebe felt relieved that her father was still there for her, eager to share the burdens and joys of their lives. She had been feeling like an exile from her own family, and could not find a way to share these feelings with Penny.

“We’ve missed you so much,” her mother said.

Peter waited as Phoebe and Penny took off their wet coats and shoes. Finally Phoebe said, “Hi Dad.”

He opened his arms and she came forward for a hug that seemed to wash away some of the pain from of the last year. He held her at arms length and said, “You look wonderful.”

“So do you, Dad.”

He actually does look pretty good, she thought. His body seemed thinner than the year before. His light brown skin was darker, and varied in color. He looked stronger, more fit. But the worry and hesitation around his eyes remained.

The sisters followed their parents through the kitchen area and past a dining room table to a couch and chairs surrounding an old oriental rug. A profusion of flowers and hanging plants served to hide the greenhouse windows on both sides. Two shockingly large paintings on stretched canvas stood in front of a curtain the formed a partition at the edge of this living space, blocking off the rest of the greenhouse from view.

Phoebe spotted an old armchair from their rooms above the toy store, and headed for it as a place of safety out of her childhood. But as she turned to sit down she felt the awkwardness of bending on her stiff knee, and a flash of pain. Out of the corner of her eye she saw her father wince.

He noticed before I even had a chance to bring it up!

Her father retreated back to a corner of the couch, where he picked up a small knife and began carving a figure with wings. He carved these wooden toys in every free moment, like a strange addiction.

“Just so no one thinks I’m hiding anything, let me say I’ve failed two courses, quit college, injured my knee again, and don’t have a job.”

Phoebe looked around with a blank face. No one spoke.

Her father casually laid his knife and wooden figure down, and crossed his legs. “I seem to remember,” he drawled as if thinking of the ancient past, “being in the same position once myself, minus the knee injury. I never did finish college.”

“And I never even started college,” put in Penny. “Although I would like to go to culinary school someday.”

“And as for the knee,” said Patti, “I’ve got a referral to an excellent specialist right next door at Middletown Hospital. I’ve got the info…”

“Mom! I’m already working with Dr. Brenner. He says I’ll get better without another operation if I take care of myself. No sports at all. And I’m following orders! My knee is improving, slowly, but that’s the best I can hope for. I’ve just got to stay with the plan.”

Phoebe cringed, afraid she had upset her mother; but Patti smiled and then laughed, saying, “I’m happy to see you’re taking charge of the situation, Phoebe.”

Her father broke into a big smile and his eyes brimmed over. He could hardly contain himself with happiness, and finally stood up and clapped his hands. “Well, if that isn’t the best news I’ve heard in a long time!”

Patti handed out cups of steaming tea and stood nearby, glancing at the two vast canvases. They were set up on milk crates to elevate them off the floor, and leaned against a wooden railing. A couple of clamp lights shone over the area. Strips of dark netting shaded the room from the sunlight that blazed through the upper glass panels on sunny days.

“So what’s your plan, now that you’re back in Middletown?” Peter asked.

“I thought I’d find some sort of job.”

“What kind?”

Phoebe intended to give an evasive answer, but her words seemed to stick in her throat. She was afraid she would burst into tears.

“We know you’re a great worker,” her father said softly, trying desperately to be helpful.

“I don’t know what to do.” Phoebe finally forced out the words.

The silence stretched on. Patti and Penny sat on the edge of their seats, watching the drama unfold, unable to play a part.

“This is about the toy store, isn’t it?” Peter asked. He frowned and looked at the ground.

Phoebe turned to her father. “I wish I could do something. I can’t help but think about… well…”

Peter looked up at her. “Go on.”

“I was talking to Sammy about how big Scutter’s Market has become, like some sort of monster eating the pizzeria and the bookstore. He told me Scutter and his investors had offered to buy him out too! But Sammy refused, and says he’ll stay open twenty more years. Now what I want to know is…”

“I know, I know.” Her father held up his hand as a stop sign. “You see the heart of the matter already. Yes, Scutter made us an offer. He even pressured me, organizing a big meeting at the Hickory Securities office with a lot of talk from Bob Bentley about making us rich. When I turned them down, they made veiled threats to drive us out. Scutter is just a pawn in this game, a front man for Milton Morphy and the Geddon Insurance Group. Geddon owns Hickory Securities and Scutter's Market.”

“I saw the article in the Standard.”

“Yes.”

“And heard them on the street when they walked out of Tuck’s sermon.”

“Alison told me. That group gets more aggressive every day.”

“What worries me most is the toy store. I can’t let them take that too!” Desperation poured out in her words.

“You’re right, you’re absolutely right!” cried her father. His voice was suddenly full of passion. “I’ve been frantic about the same thing. But let me tell you, we sold to Gilligan with an agreement that he cannot sell to either Scutter or his backer Milton Morphy, or to any concern in which they have an interest.”

Phoebe listened carefully, and studied her father’s expression. “But you’re worried anyway,” she probed him.

“I have to admit it. Every day I wonder if Gilligan, in all good faith, might sell the store to someone who secretly knows this information, who then would turn around and sell to Scutter or one of their front businesses. I’ve heard rumors that Gilligan is under financial pressure. He got divorced a few months ago, and the store is not taking in the kind of money he counted on.” Peter frowned. Deep vertical lines ran down the middle of his forehead. “Now I wish we’d just rented to him – although I’d be back running the place if we’d done that.”

“I thought you were getting away from it all. You seem more involved than I thought.” Inside her heart, Phoebe was celebrating. She had imagined this conversation several times, and it was going better than she hoped.

“You’re right,” Peter was saying. “We are involved, just in a different way. We’ve only been pretending to be retired this past year… Oh, don’t act surprised.”

No one spoke. The rain murmured on the greenhouse roof. A pot on the stove was giving off steam, and the scent of cooking filled the warm air.

“Can I jump in here?” asked Patti. “I’ve gone to a lot of trouble to set up these paintings – and it looks like I’ll have to take them down right away – so let me use them now to help Phoebe understand what’s going on.”

Phoebe had been curious about the paintings since she arrived, and now gave the vast canvases her full attention.

One was tall and narrow and the other a wide rectangle. Both rose a couple of feet above her mother as she stood next to them. The wide rectangle – at least twelve feet across – was obviously a kind of map of Middletown and the forest, an aerial view as if painted from a low-flying airplane.

The second painting was also an aerial view, but of a valley she had never seen, a strip of land stretching out like a green road surrounded by dark hills and ridges. The valley had a strange radiance. Its velvety green texture seemed to shimmer and glow in the sunlight. A small stream appeared from the hillside below, twinkled like silver through the deep green on trees and meadows, and then disappeared into the hills beyond.

“Whoa, Mom!” said Phoebe in an awed voice. “I’ve never seen anything like these before. How could you know every house and tree for miles?” She looked at her mother, who was smiling off to the side. “Really, they look great. I heard about your show coming up. People will love these.”

Her mother was obviously pleased. “I was hoping to impress you. They took me most of the winter and spring, and it’s true, I’ve been working up to them for years. It’s sad, though, because I can’t show them. That’s the frustrating part of this strange life we’re leading. This place,” she tapped the edge of the tall painting, “is a secret. And even part of this one too. We can’t let most people see them.”

“How is anyone going to see them back here in the greenhouse?”

“Jerome Peabody from the Standard keeps trying to interview us. Alison says he’s snooping around.” Patti’s face seemed to cloud over, struggling with her own thoughts.

“So you and Dad have been staying out in the forest for some reason,” Phoebe offered.

No one spoke. Thunder cracked overhead, and the downpour drummed against the glass.

“Do you remember Wendy?” Patti asked suddenly. “She used to be around when you were little. She came by the store from time to time.”

“Of course…” Phoebe’s expression changed, as if a light were shining where there had been darkness. Of course… of course. Why didn’t I think of Wendy? “How could I forget her, Mom? She helped Alison with the herbs, she cured my bronchitis over and over, she came to Protectors of the Wood meetings, she gave us that special Breakfast Mixture tea. Whatever happened to her? I haven’t seen her in years.”

Her mother gestured towards the tall painting. “Many years ago this part of the forest – called Hidden Valley – was owned by Wendy’s grandfather. Part of the family is still alive and living there, remaining hidden all these years, growing their own food and living surprisingly well. They are related to the Half Moon People, who farmed the land from here to the sea long ago. Wendy has lived there her whole life, except for the time she’s spent here at the Garden Center. In fact, the land in this painting is still their property, if they could only prove it. Many of the Half Moon People moved to Rivergate, over near the Wetland Preserve. That’s all a long story for another night; but right now you should know that they are the center of the Protectors of the Wood, our foundation that supports the forest. They are the leaders of what we’re doing.”

Patti looked closely at Phoebe, who was processing this information like lightening. Missing pieces of the puzzle had fallen into place. The picture had suddenly grown much larger and more detailed in her mind. The painting before her came alive.

“Everyone must be starving!” exclaimed Patti suddenly. “Alison and Chi Chi should be here soon, and the chicken is almost ready. We’ve got the world’s best greens and early tomatoes from the forest, and we carried these raspberries as if they were made of gold!”

“The are like gold,” said Penny. “I’m going to put them in my breads and muffins. Sammy will love it.”

Phoebe took two giant handfuls and began dropping them into her mouth like peanuts. Her father approached her from the side and whispered in her ear, “Hey, let’s shoot a few arrows before dinner.”

“Okay, I’d love to,” she murmured back quietly.

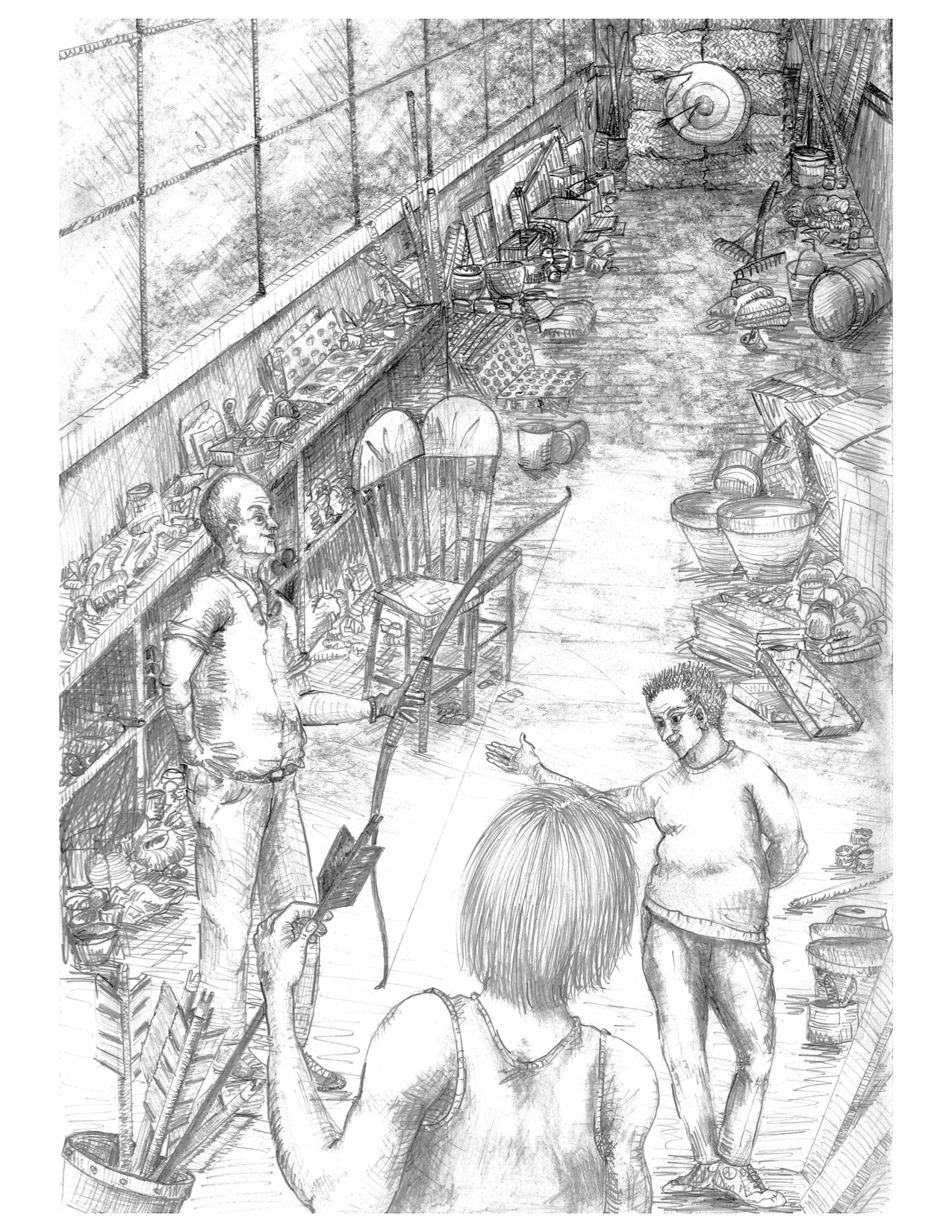

They made their escape from the dinner preparations and walked around the side of Patti’s two paintings and past a curtain into a darkened section of the greenhouse. Peter flipped a switch, and hanging florescent lights came alive and shone over long rows of shelving on either side of an aisle, all cluttered with plastic trays full of small containers for starting plants. But nothing green was left in the thirty-yard stretch of greenhouse. At the end of the aisle an archery target was stuck to a wall of hay bales.

Phoebe stared at the seemingly endless litter of trays piled up in disorder. “What’s all this for?” she asked.

“Oh what a mess,” her father sighed. “I’ve got to wash everything and store it for next year. I just can’t get to this job yet.”

“There’s so much of it.”

“It’s our new project. Thousands of plants, all from Wendy’s seeds. It’s a pretty daring move – several acres of planting that’ll be ready for market soon. Tomorrow I’ll show you something that’ll give you a better idea of what we’re doing.”

As he was talking Peter led the way down the aisle past the hay bales and there at the end of the greenhouse a few bows and quivers full of target arrows hung from hooks near the door.

“Your old bow is still ready to go,” her father said, and handed her a long recurve bow a little less than her own height. “I’ve been shooting it every few weeks to keep it ready,” he told her, and grabbed his own bow and arrows and a couple of gloves. They walked back to a small open space with a few wooden chairs. “Go ahead, take a shot,” he said.

“Penny tells me you’ve been practicing, and I haven’t drawn a bow all year.”

“We’re not keeping score. Just enjoy it.”

She pulled an arrow from the quiver and put it on the bow, knocking the back end onto the string. Her chest heaved with a deep sigh. She stood sideways to the target and slowly drew the bow, three fingers gripping the string, staring down the arrow to the bull’s eye. Gently she released her fingers and the arrow buzzed down the long greenhouse into the third circle from the center.

“All right!” cried Peter. “Not bad for your first shot in a year. I’ve missed doing this with you.”

He moved into position, knocked an arrow, and let it fly all in a few seconds. It buzzed effortlessly into the center of the target.

“May I join this illustrious group?” came a voice nearby.

“Chi Chi!” exclaimed Phoebe. “You always appear suddenly like this! How do you do it?”

Behind them stood an unusually tiny man with pointed ears and chin. His short hair was gray, and his face was smooth and almost free of wrinkles. He reminded Phoebe of an elf or leprechaun.

Chi Chi inclined his head and shoulders to Phoebe as a mark of respect, and then said, “So good to see you back among us.” He smiled and rubbed his hands together. “Yes, yes, we haven’t had this pleasure in ages. Go ahead, try again,” he told her.

She pulled another arrow from the quiver and set it on the bow, noticing with surprise that the arrow was black. The wood seemed to be stained with a dark substance, and the feathers were a dull black, the color of a crow.

“A black arrow!” she said, studying it with curiosity. “I never saw one of these before.”

“Only Chi Chi makes them, “ said Peter. “He does it to amuse me, but it shouldn’t be here. We keep them in the forest.”

"It’s our sign,” explained Chi Chi. “The sign of our project.”

Phoebe could not take her eyes off the arrow. She had read The Black Arrow by Robert Louis Stevenson many times, and knew exactly what the symbol meant. It referred to the efforts of oppressed men to claim their heritage, and their battle against the greed of their oppressors. Her father had given her the book as a child.

“It’s from the book,” she said with excitement.

Chi chi bowed his head to Phoebe, and then offered Peter a mysterious knowing smile.

Phoebe studied the black arrow for a moment. The Protectors of the Wood had just jumped to the top of her list of things to learn more about. She carefully drew the bow and shot. The arrow thumped into the target about an inch from the center. The men clapped.

“Dinner!” Penny yelled through the curtain.

“You go ahead,” said Peter. “Chi Chi and I will put things away.”

Phoebe walked back to the curtain, her mind spinning with excitement and surprise. She opened the curtain to the noise of voices. Patti, Alison, and Penny were setting the table, their backs to Phoebe.

“So how are you handling it?” Alison was asking.

Her mother mumbled something about “the source,” and then the words, “She doesn’t know, we’re leaving it alone.”

“Is that wise?” Alison asked. “Remember what John said.”

Phoebe was immediately certain that they were talking about her. She stepped back, letting the curtain close. What don’t I know? She asked herself. And who is John? What could it possibly be, that they’re all hiding from me?